German ambition in the late 1930s extended beyond political and military spheres; it also encompassed technological dominance, particularly in the realm of speed and engineering prowess. At the heart of this ambition was the Mercedes-Benz T80, a project born from the fervent desire of German auto racer Hans Stuck to seize the world land speed record for both himself and Germany. In 1937, Stuck successfully persuaded Wilhelm Kissel, Chairman of Daimler-Benz AG, to embark on the ambitious undertaking of developing and constructing a vehicle specifically designed for this purpose. The engineering genius of Dr. Ferdinand Porsche was enlisted for the design, ensuring the project was grounded in cutting-edge automotive expertise. Adding further weight to the endeavor, Stuck secured approval from Adolf Hitler himself, who recognized the immense propaganda potential of a German land speed record, viewing it as a powerful demonstration of Germany’s supposed technological superiority on the world stage.

Officially designated the Mercedes-Benz T80, or Type 80, this groundbreaking vehicle was initially conceived by Dr. Porsche with a target speed of 342 mph (550 km/h), a staggering figure for the era. This initial target was predicated on utilizing an engine capable of producing 2,000 horsepower (1,490 kW). However, as rival contenders in the land speed record arena began pushing the boundaries further, the ambitions for the T80 were escalated accordingly. Mercedes-Benz engineers responded by extracting even greater power from the engine. By 1939, as the T80 neared completion, the target speed for its record attempt was dramatically increased to 373 mph (600 km/h), intended to be achieved after a 3.7-mile (6 km) acceleration run.

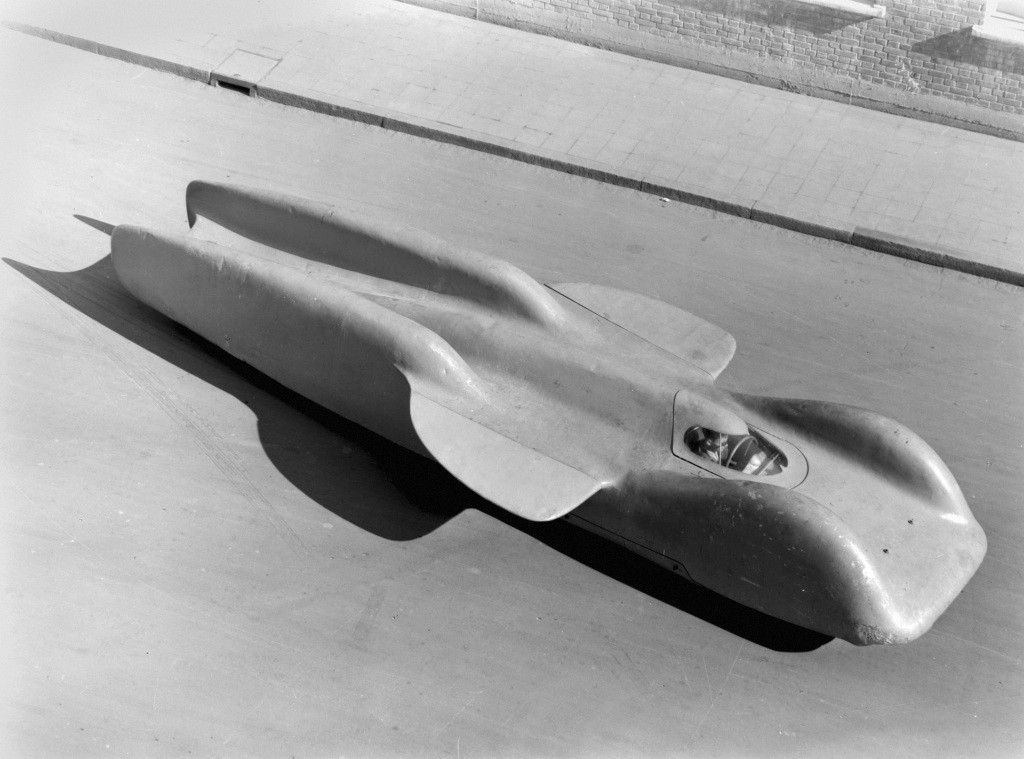

The financial commitment to the T80 project was substantial, totaling 600,000 Reichsmarks – an investment equivalent to approximately $4 million in today’s US dollars. To realize the extreme speeds envisioned, aerodynamics became paramount. Renowned specialist Josef Mikcl was brought in to meticulously sculpt the car’s body, with the actual construction entrusted to aircraft manufacturer Heinkel Flugzeugwerke, leveraging their expertise in lightweight and aerodynamic structures. Porsche’s design incorporated a fully enclosed cockpit for driver protection and reduced drag, a low-sloping hood to minimize frontal area, and elegantly rounded fenders that seamlessly integrated into the overall form. To enhance high-speed stability, the rear wheels were partially enclosed within elongated tail fins, acting as stabilizers. Furthermore, two small wings were strategically positioned at the mid-section of the car to generate downforce, crucial for maintaining grip and control at extreme velocities. This intensive focus on streamlining resulted in an exceptionally low drag coefficient of just 0.18 for the twin-tailed body – a remarkable achievement that remains impressive even by contemporary aerodynamic standards.

The T80’s innovative design extended beneath its skin. It featured a tri-axle configuration, with the front axle dedicated to steering and the two rear axles providing the driving force. Powering this land-speed behemoth was a colossal 2,717 cu in (44.5 L) Daimler-Benz DB 603 inverted V-12 aircraft engine. This engine, a prototype DB 603 V3, was personally provided by Ernst Udet, then director of Germany’s Aircraft Procurement and Supply, underscoring the project’s national importance. The DB 603, a supercharged engine with mechanical fuel injection, was specifically tuned to deliver a monumental 3,000 hp (2,240 kW) for the record attempt. It ran on a highly specialized and exotic fuel mixture comprising methyl alcohol (63%), benzene (16%), ethanol (12%), acetone (4.4%), nitrobenzene (2.2%), avgas (2%), and ether (0.4%). To further enhance performance and prevent engine knock, MW (methanol-water) injection was employed for charge cooling and anti-detonation.

Power from the DB 603 engine was channeled to all four drive wheels via a hydraulic torque converter coupled to a single-speed final drive. To manage the immense power output and maintain traction at record speeds, the T80 was equipped with a sophisticated mechanical “anti-spin control” system. This system utilized sensors on both the front and rear wheels to detect any instances of wheel spin. If the rear wheels were detected to be rotating faster than the front wheels, indicating loss of traction, the system would automatically reduce fuel flow to the engine, effectively mitigating wheel spin and maintaining control.

In terms of sheer size, the Mercedes-Benz T80 was a leviathan. It measured an impressive 26 ft 8 in (8.128 m) in length and stood 4 ft 1 in (1.245 m) tall. The body width was 5 ft 9 in (1.753 m), expanding to a substantial 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) when including the stabilizing wings. All six wheels were of considerable size, measuring 7 in x 32 in, and the vehicle had a track width of 4 ft 3 in (1.295 m). Despite its massive dimensions, the T80 was relatively lightweight for its size, weighing in at approximately 6,390 lb (2,900 kg), thanks to advanced materials and construction techniques.

The T80 project even garnered a dramatic, albeit unofficial, nickname from Hitler himself: “Schwarzer Vogel,” meaning “Black Bird.” The vehicle was intended to be painted in the German nationalistic colors of the time, complete with the German Eagle and Swastika insignias, further emphasizing its propaganda role. The designated driver for the record attempt was Hans Stuck, who was to pilot the T80 on a specially prepared stretch of the Dessau Autobahn (part of today’s modern A9 Autobahn). This section of highway was 82 ft (25 m) wide and 6.2 mi (10 km) long, with the median strip paved over to create a wide, smooth surface for the high-speed run. The record attempt was initially scheduled for January 1940, and it would have marked the first-ever absolute land speed record attempt to take place in Germany.

However, the grand ambitions for the Mercedes-Benz T80 were abruptly curtailed by the outbreak of World War II. The impending conflict brought the project to a standstill, with the T80’s final touches never completed, and the car never achieving a run under its own immense power. With the record attempt canceled, the T80 was relegated to storage. In late February 1940, the valuable DB 603 engine was removed, and the vehicle itself was relocated to Karnten, Austria, where it remained in storage throughout the duration of the war, effectively hidden from the world. The Mercedes-Benz T80 remained largely unknown outside of Germany until its rediscovery by the Allied forces after World War II. Remarkably, the T80 emerged from the war relatively unscathed, a testament to its robust construction and careful storage. In a fitting tribute to its engineering significance, the T80 was eventually moved to the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, where it is now a permanent and iconic exhibit within the Silver Arrows – Races & Records Legend room, allowing visitors to marvel at this extraordinary machine. (Currently, only the T80’s body is on public display, with the chassis stored in a museum warehouse.)

The legacy of the Mercedes-Benz T80 extends beyond its unrealized record attempt. On 16 September 1947, John Cobb, driving the twin Napier Lion-powered Railton Mobil Special, achieved a speed of 394.19 mph (634.39 km/h), finally exceeding the T80’s calculated target speed for the Autobahn run. However, upon discovering the T80 after the war, Allied engineers were quoted an astonishing estimated top speed of 465 mph (750 km/h) for the German machine. Had the T80 indeed been capable of reaching this projected velocity, it would have set a record that would have remained unbroken until 1964, when Craig Breedlove surpassed it with a speed of 468.72 mph (754.33 km/h) in the jet-powered Spirit of America. Even today, the Mercedes-Benz T80 would still hold the distinction of being the fastest piston-engined, wheel-driven vehicle ever conceived, a testament to its groundbreaking engineering and enduring appeal as a symbol of unfulfilled ambition in the pursuit of speed.

OFFICIAL PRESS RELEASE

The Mercedes-Benz T 80 world record project car was conceived by racing driver Hans Stuck with the singular ambition of breaking the absolute world land speed record. Stuck successfully assembled a formidable team to bring his vision to life, enlisting the support of three key figures: Wilhelm Kissel, the Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz AG; the brilliant engineer Ferdinand Porsche; and air force general Ernst Udet. Throughout the 1930s, each of these influential individuals played a crucial role in propelling the project towards completion. The story of the Mercedes-Benz T 80 is a testament to the dedication and perseverance of its designers and aerodynamicists, a marathon endeavor that commenced in 1936 and extended until 1940 – ultimately concluding without the T 80 ever being put to its intended use.

The overarching objective of all those involved was to achieve a speed unprecedented for any land-based vehicle. This ambition was made even more challenging by the relentless pace of record-breaking attempts by British drivers during this period, primarily at Daytona Beach and the Bonneville Salt Flats. On 3 September 1935, Malcolm Campbell reached a speed of 484.62 km/h over the flying mile with his iconic “Blue Bird.” On 19 November 1937, George Eyston shattered the 500 km/h barrier with “Thunderbolt,” achieving 502.11 km/h over the flying kilometer. And finally, on 23 August 1939, John Cobb established a new benchmark of 595.04 km/h over the flying kilometer with the “Railton Special.” In response to these escalating records, the planned target speed for the T80 was progressively revised upwards, initially from 550 km/h to 600 km/h, and ultimately reaching an ambitious 650 km/h.

A New Record for the Silver Arrows

Success in the T80 project would have added another illustrious chapter to Mercedes-Benz’s already rich history of speed records. A particular highlight to date was Rudolf Caracciola’s record-breaking run on public roads on 28 January 1938, where he achieved a speed of 432.7 km/h with the Mercedes-Benz W 125 record car on the autobahn near Darmstadt. Despite the potential glory, the T 80 project was not without its internal critics within Mercedes-Benz. A significant point of contention revolved around Hans Stuck himself. During the 1930s, Stuck was a prominent Grand Prix racing driver for Auto Union, a direct competitor to Mercedes-Benz. Company decision-makers questioned how the public would perceive the Stuttgart racing department engaging a driver from a rival team for such a high-profile world record attempt. Many within the company wondered if it would be more appropriate to entrust the record attempt to their own works driver, Rudolf Caracciola, as had been the previous practice.

However, Stuck also possessed historical ties to the Mercedes-Benz brand. In 1931 and 1932, he had raced with considerable success for Mercedes-Benz, driving a Mercedes-Benz SSKL. His achievements included becoming the international Alpine champion and Brazilian hill-racing champion in 1932. By 1936, Stuck was leveraging his earlier connections with Untertürkheim to advance his land speed record ambitions.

Through his contacts within the Auto Union racing department, Stuck established a connection with the renowned designer Ferdinand Porsche. Porsche’s “P-vehicle” concept had served as the foundation for Auto Union’s Grand Prix racing cars from 1934 to 1936. Furthermore, Stuck had a pre-existing relationship with flying ace Ernst Udet, dating back to the 1920s. During that era, Stuck and Udet would often engage in friendly rivalries, such as ice races on the frozen Lake Eib near Garmisch-Partenkirchen, with Stuck driving an Austro Daimler racing car and Udet piloting an aircraft.

Telegram to Stuttgart

What fueled Stuck’s unwavering desire to break the absolute world land speed record? One key motivator was undoubtedly his Auto Union teammate, Bernd Rosemeyer. Following Rosemeyer’s triumph in the 1936 European Grand Prix championship, Hans Stuck began seeking a new platform to showcase his own exceptional driving skills. The world land speed record, then dominated by British drivers, presented itself as an enticing and prestigious opportunity.

Stuck’s connections extended into the National Socialist government, providing him with confidence in securing political backing for this ambitious prestige project. However, he also recognized the critical need for technical partners to bring his vision to fruition. On 14 August 1936, Stuck sent a telegram from Pescara to Wilhelm Kissel, the Chairman of the Board of Management of Daimler-Benz, requesting a meeting. In their subsequent conversation, Stuck proposed that Mercedes-Benz undertake the construction of a record-breaking vehicle powered by a Daimler-Benz aircraft engine. He pointed out that British record-breaking cars of that era also relied on powerful aircraft engines for their performance.

Record-breaking attempts were not unfamiliar territory for Mercedes-Benz. The Stuttgart-based company had already established numerous records throughout the 1930s. As Kissel recalled, the concept of building a record-breaking vehicle utilizing an in-house aircraft engine had previously been considered under the leadership of the late Daimler-Benz board member Hans Nibel, who had passed away in 1934.

The design of the record-attempt vehicle was entrusted to Ferdinand Porsche, who had departed from his position as Chief Engineer at Mercedes-Benz in 1928. Despite his departure, connections remained between the world’s oldest automobile manufacturer and Porsche’s design studio (P.K.B.). Notably, between 1936 and 1937, Mercedes-Benz built 30 prototypes of the “KdF” car, which would later enter series production as the iconic VW Beetle after the Second World War.

On 11 March 1937, Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche GmbH formalized its collaboration with Daimler-Benz AG through a contract for extensive involvement in all facets of engine and vehicle design. Beyond the T 80 (where the “T” in Porsche nomenclature stood for “type”), the resulting projects encompassed the T 90, T 93, T 94, T 95, T 97, T 104, and T 108. Thus, Porsche’s involvement extended beyond the world record project vehicle to encompass the development of racing cars, commercial vehicles, and engines for Mercedes-Benz.

An Aircraft Engine for a World Record

The T 80 was slated to be powered by a Daimler-Benz aircraft engine. However, procuring such an engine was not a straightforward matter, as the Ministry of Aviation held exclusive rights over the allocation of all aircraft engines produced in Germany. To overcome this hurdle, Stuck leveraged his relationship with Ernst Udet, who had by then ascended to the position of head of the Luftwaffe’s technical department.

Fritz Nallinger, Daimler-Benz’s technical director responsible for the design, development, and production of large engines at the time, provided his expert assessment of the project in September 1936. Nallinger estimated that an output of 1,103 kW (1,500 hp) was realistically achievable with the initially proposed DB 601 aircraft engine. In fact, a remarkable 2,036 kW (2,770 hp) was ultimately attained with a modified version of this engine, specifically prepared for flight record attempts in 1938 and 1939, showcasing the engine’s immense potential.

In October 1936, Kissel informed Porsche via telephone that the Ministry of Aviation had agreed to release two engines for the T80 project. He also formally requested Porsche to commence work on the vehicle’s design. The official order was placed on 13 January 1937. An appended clause to the order stipulated that the Porsche design was to be consistently referred to as a Mercedes-Benz world record project vehicle, emphasizing the collaborative nature of the endeavor.

The initial financing arrangements were structured as follows: Daimler-Benz would assume responsibility for the costs associated with building the chassis. The construction and funding of the body were to be undertaken by aircraft manufacturer Heinkel. The organization and financial burden of the record-breaking attempt itself would be borne by racing driver Hans Stuck. These terms were initially outlined by Kissel during his meeting with Stuck on 21 October 1936. In November 1936, Kissel estimated that the T 80 project could not be completed before October 1937, highlighting the ambitious timeline and complexity of the undertaking.

In February 1937, the project achieved a significant milestone when Ernst Udet officially approved the release of the DB 601 aircraft engine for installation in the T 80. As the development progressed and greater power requirements became apparent, this initial approval was subsequently extended to encompass the more powerful DB 603 V3 engine, ensuring the T80 had access to the necessary performance to achieve its ambitious speed targets.

On 6 April, Porsche presented his detailed plans for the T 80 in Untertürkheim. These plans outlined a phased development process, progressing from an initial twin-engine proposal to a final single-engine concept. This refined proposal already exhibited most of the defining characteristics of the vehicle that was ultimately constructed: a three-axle record-breaking car propelled by a centrally mounted V12 aircraft engine. Porsche’s calculations indicated that achieving a record speed of 550 km/h after a five-kilometer acceleration distance would necessitate an engine output of at least 1,618 kW (2,200 hp), with an even more desirable target of 1,838 kW (2,500 hp) to provide a safety margin and ensure success.

The initial plan was to conduct the record-breaking attempts on a track located in the United States of America, leveraging the established infrastructure and favorable conditions. However, by mid-1938, this plan was revised in favor of using a specially prepared section of the autobahn between Dessau-South and Bitterfeld in Germany. In August 1938, the General Inspector of German Roads, Fritz Todt, announced that the designated section of the autobahn would be available for use in October 1938, setting a potential timeline for the record attempt.

The question of the definitive location for the record attempt remained somewhat unresolved. Discussions about a potential record attempt in the USA resurfaced in 1939. The Bonneville Salt Flats in the USA had become the established venue for world speed records in recent years. One factor contributing to the renewed discussion at Mercedes-Benz may have been concerns regarding the challenging driving conditions presented by the manually paved median strip between the two lanes on the envisioned section of the autobahn, potentially impacting the stability and predictability of the high-speed run.

The Birth of the World Record Car

The T 80 project steadily materialized throughout 1938. In October, Ferdinand Porsche, accompanied by his team, inspected the wooden model of the bodyshell, marking a crucial step towards realizing the vehicle’s aerodynamic form. The focus then shifted to specifying the types of steel paneling for the body and generating a corresponding bill of materials, finalizing the details of the driver’s seat and cockpit, and defining the tubular structure of the spaceframe chassis. On 26 October 1938, the Mercedes-Benz racing department documented in a test report that the first welded frame weighed 224 kilograms, indicating progress in the chassis construction.

The chassis and frame were completed by the end of November 1938. The Mercedes-Benz racing department projected that the vehicle, complete with all its major assemblies, would be ready by the end of January 1939. A memo dated 26 November 1938 indicated that if the aircraft engine could also be delivered by that timeframe, the chassis assembly could be completed by the end of February 1939, with the bodywork expected to be finished by May 1939, outlining a detailed production schedule for the ambitious project.

Will the Tires Withstand the Record-Breaking Speed?

Tyre manufacturer Continental rigorously tested the wheels intended for the T 80 on a specialized test stand. During a high-speed test at 500 km/h in January 1939, they observed significant deformation of the wire-spoked wheels supplied by Hering in Ronneburg (Thuringia), raising concerns about their suitability for the extreme speeds envisioned. By May, while improvements had been made, slight deformations were still detected at 480 km/h, necessitating further refinement and testing to ensure tire integrity at record-breaking velocities. Meanwhile, Porsche had calculated that a distance of between 13.73 kilometers (with 2,023 kW/2,750 hp) and 11.48 kilometers (with 2,206 kW/3,000 hp) would be required for a successful record-breaking run at 600 km/h, emphasizing the immense power and acceleration needed to reach and sustain such speeds.

In 1939, the decision was made to equip the T 80 with the more powerful DB 603 engine. Although the Ministry of Aviation had halted its further development as an aircraft engine in March 1937, it granted permission for its use in the land speed record attempt, recognizing the project’s national prestige. Engineers were confident that the 44.5-liter V12 aircraft engine, initially designed for an output of around 1,471 kW (2,000 hp), could be tuned to reach up to 2,206 kW (3,000 hp) at 3,200 rpm for the record attempt. To achieve this enhanced output, the engine was to be fueled with two specialized racing fuels, designated XM and WW, formulated for maximum performance. From February 1940, the company received authorization to resume work on the DB 603 as an aircraft engine, with series production for aviation applications commencing in 1941, highlighting the engine’s dual purpose and eventual contribution to the war effort.

Optimization of the DB 603 for the Record Attempt

In 1939, racing manager Alfred Neubauer noted that a DB 603 engine for the T 80 could be delivered as a “running-in engine” in June of that year. The engine intended for the actual record attempt was projected to be available by the end of August 1939, indicating a phased engine delivery schedule. In June, Fritz Nallinger, responsible for Daimler-Benz aircraft engines, implemented various refinements to optimize the DB 603 for installation in the world record project vehicle. These modifications included adjusting the routing of the air intake ducts and configuring the exhaust ducts to enable the vehicle to harness recoil energy and convert it into forward momentum, showcasing innovative engineering approaches to maximize performance.

During the summer of 1939, wind tunnel measurements were conducted on a scale model of the T 80 at the Zeppelin company in Friedrichshafen. The primary objective of these tests was to determine the optimal level of downforce. The goal was to achieve sufficient downforce to effectively transfer the engine’s immense power to the road surface, while simultaneously minimizing downforce to avoid overloading the tires, which featured thin tread surfaces designed for high-speed running. Following these wind tunnel tests, the surface area of the downforce fins was further reduced by 3.65 square meters, reflecting the iterative refinement process aimed at achieving aerodynamic equilibrium.

Testing of the T 80 continued even after the outbreak of the Second World War on 1 September 1939, underscoring the project’s initial momentum and the ongoing commitment despite the escalating global tensions. On 12 October, for instance, the chassis of the world record project car underwent testing on a roller dynamometer to evaluate its mechanical performance. In light of John Cobb’s new record of almost 600 km/h, Porsche was by this time envisioning a target speed of up to 650 km/h for the T80’s record attempt, pushing the boundaries even further. This increased target speed would likely necessitate an engine output of up to 2,574 kW (3,500 hp), a staggering power level. However, engineers believed that even this extreme level of power output was potentially achievable with further refinements to the DB 603 engine, demonstrating their unwavering optimism and commitment to pushing the limits of engineering.

End of the T 80 Project in Spring 1940

Ultimately, no further progress was made towards realizing the world land speed record attempt. As early as February 1940, with the war intensifying and resources being redirected, Mercedes-Benz initiated an inquiry to the Ministry of Aviation regarding potential financial contributions towards the substantial development and production costs incurred by the T 80 project. In June 1940, a final project report was produced, marking the formal conclusion of the ambitious endeavor, and the T 80 was placed into storage, its record-breaking aspirations unrealized. The DB 603 world record project engine, which had been installed in the vehicle, was subsequently returned to the Ministry of Aviation, its potential for land speed glory now repurposed for wartime applications.

After the Second World War, the Mercedes-Benz T 80 was brought out of storage and prominently exhibited in the company’s museum in Untertürkheim, becoming a captivating artifact of automotive history. When the museum underwent a reorganization in 1986, the body and chassis of the T 80 were separated, and the chassis was placed in storage, while the iconic body remained on display. The new Mercedes-Benz Museum, which opened in 2006 just outside the gates of the Untertürkheim plant, continued to showcase the T 80 in its permanent exhibition, presenting its original body, spaceframe, and wheels – albeit without the heavy chassis, offering visitors a glimpse into the engineering marvel of this unfulfilled dream.

The body of the T 80 displayed in the Mercedes-Benz Museum intentionally preserves the traces of the project work that remained unfinished in 1940, offering a poignant reminder of the project’s abrupt termination. Mercedes-Benz Classic is now juxtaposing the chassis, along with a replicated spaceframe and a sectioned engine, with this remarkable exhibit. Since mid-2018, this unique display arrangement has aimed to make the advanced technology of the T 80 more immediately and impressively accessible to museum visitors, ensuring that the legacy of this extraordinary machine continues to inspire and captivate automotive enthusiasts and historians alike.